Congratulations on adopting or fostering a rescue dog! As a new caretaker, there are probably a thousand questions going through your mind. Where will the dog sleep? Do I need a crate? Is the dog housetrained? What kind of food do I feed? Do I walk with a collar or harness?

Being prepared is important and you may find that your dog adapts to a new life relatively smoothly. However, it’s rare that you won’t hit a few bumps in the road. Once you bring the dog home, the best thing you can do is give the dog some time to get used to the new surroundings by supporting them one day at a time. It’s easy to get caught up in the excitement of having a new dog or puppy. Your heart may be filled with visions of all the fun and wonderful activities that you will enjoy together. Perhaps you will fulfill these visions at some point in the future, but one of the biggest mistakes you can make with a rescue dog is expecting too much too soon.

The reality is that many dogs are surrendered to the shelter or rescue group because the caretaker expected the dog to be just like the family dog they had growing up or be as gentle and friendly with children as their neighbor’s sweet golden retriever. They may have tried training methods that “worked” on their previous dog not for this one. Like humans, every dog is an individual with a unique learning history and personality.

Denise Fenzi has a wonderful quote:

“Instead of wishing for that magical dog, work with the one that you have right now, the one right there, looking up at you.”

Training orchids

I’ve been the Staff Trainer at the Humane Society of Westchester since 2016. The shelter takes in dogs from animal care and control officers, local surrenders, and from other shelters from the South and Midwest. I see dogs come in with a range of personalities and behavior issues. Some are super friendly, confident, and are able to go with the flow easily. I don’t worry about these dogs much, mostly because my time is better spent working with the dogs who are more like orchids and need delicate care to thrive.

I often have little to no information about a dog’s history other than the location they came from. Frankly, knowing some history about the dog is a luxury. In some cases, the dogs have spent their entire lives outdoors and have never seen the inside of a home or vice versa. More commonly for shelters in metropolitan regions like New York, the transported dogs have grown up in much quieter environments that are completely different than the urban and even suburban environments they find themselves in now. I’ve seen so much tragedy; dogs rescued from hoarding situations, puppy mills, and other types of abuse and neglect. Sometimes, the dog has been at the shelter for a long time, overlooked because they are too old, not a puppy, not the right look, not hypo-allergenic, exhibit challenging behavior issues, or have health issues. I’ve come to accept the fact that I cannot change the past and will never know how or why a dog ended up homeless, mistreated, neglected, or abandoned. Instead, I focus my energy on moving forward and writing a new story that begins with hope.

Avoid system overload

For a dog entering a new home, there are multiple novel stimuli bombarding the dog’s senses at once. There’s the strong smell of household cleaners, pounding of children’s feet running around, lights reflecting off the floor, an unexpected image of a dog in a full-length mirror, and the sound of a skateboard rolling down the driveway.

New routines have to be learned including where to sleep, when to eat, what to play with, what not to chew on, and where to go potty. The humans usually don’t make it any easier by changing their minds several times before finally settling on a system. In addition to adjusting to a new environment and learning routines, dogs are integrating themselves into a new social group. The process includes learning how to communicate and developing relationships with individual group members, each fairly daunting tasks on their own. Keep in mind that dogs who are recovering from physical or emotional trauma may also need additional time to heal.

While most people understand it takes at least a little time for a dog to adapt to a new home, please seek the help of a qualified professional with experience in treating behavior related to fear or anxiety if the dog is trembling, salivating, tucked into a ball, or hiding. I’ve heard too many people say that a dog is just a little “shy” or “will grow out of it” and avoid or delay treatment to relieve emotional suffering. In fact, their fear worsens with time.

Take it slow

Starting off on the right foot can make a huge difference. To help make the transition go as smooth as possible, it is important to give your rescue dog time to decompress once they are home. Allow the dog’s nervous system the time it needs to recover from stress and process the rapid changes they are going through. Stress on the dog can overtax their nervous system, resulting in adverse reactions, and eventually reduces their fitness (Broom and Johnson 2019).

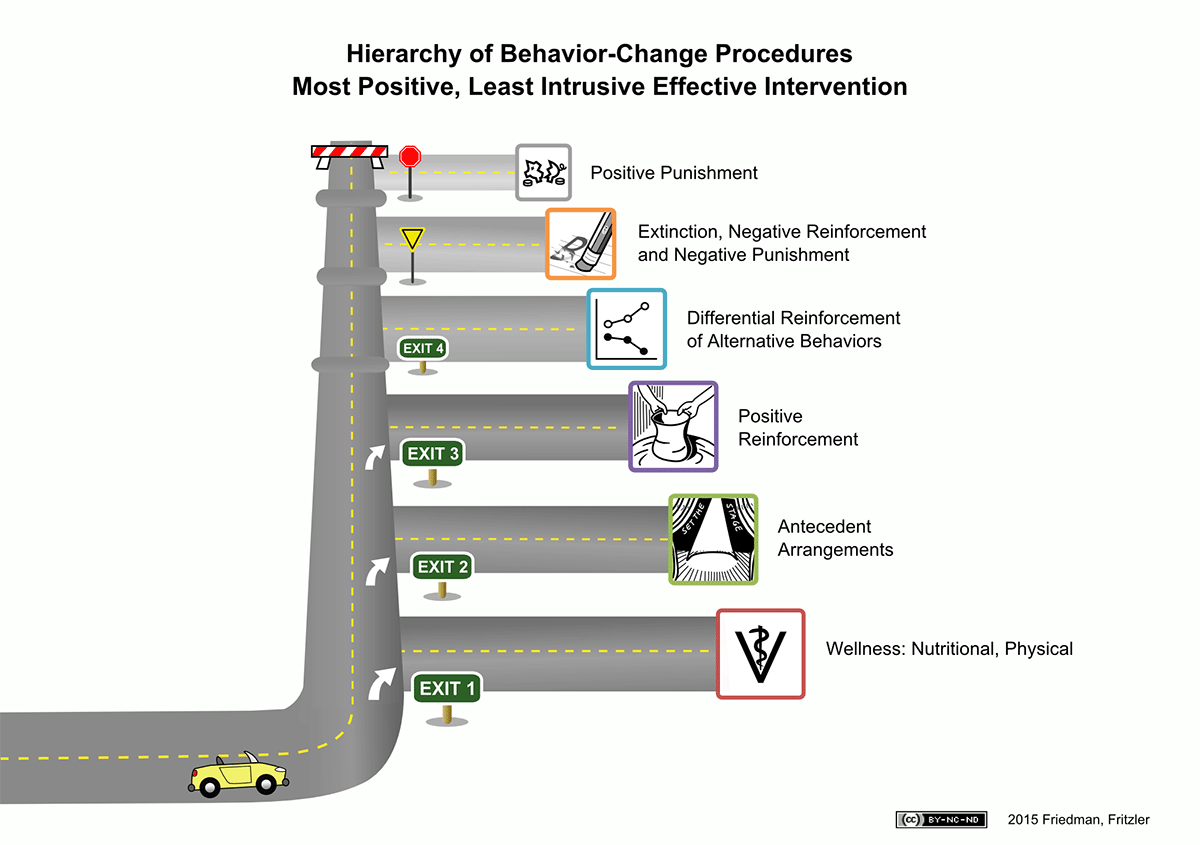

I follow Dr. Susan Friedman’s Humane Hierarchy (Figure 1) model of intervention strategies. The first level is to fulfill the dog’s physical and nutritional needs. A dog that has been damaged by psychological or physical trauma cannot effectively heal without a healthy physiology. At my shelter, the staff will examine the dog and coordinate with the vet for any necessary medical treatment. If the dog is physically healthy enough for adoption, evaluations are performed to inform decisions regarding the type of home for placement and whether the dog needs behavior training before adoption. Then I proceed with the model as a guide to find the most positive and least intrusive interventions to modify behavior. This roadmap helps practitioners choose training methodology, ensuring that animal welfare is accounted for well before training begins. I’ll share two true stories about two special dogs to show you what this may look like.

Figure 1. Humane Hierarchy by Susan Friedman.

Duchess’s story

Duchess was a young female mixed breed found as a stray in North Carolina. She arrived at HSW in October 2018. She was emaciated, malnourished, and covered with mange. Before training could start, we had to help her get healthy and add some weight. It took about a month for her to heal physically. Once she was healthy enough to participate in normal doggy activities, I started working with her. It was clear that she loved to play with dogs and was fairly comfortable with most humans. However, she was terrified of household items like garbage cans and step ladders. She hid from anything that was novel to her. Before she could be adopted, I implemented a behavior therapy plan to help her overcome her fears. It took about 6 months of training progressing at Duchess’s pace. I made sure she felt comfortable and safe while exposing her to her triggers and other novel stimuli. Finally in May 2019, the perfect family adopted her. They understood that she may struggle with new experiences and novel objects and I continued to help them post adoption. They were willing to be patient and committed to following through with her training plan which made the adoption successful.

Henry’s story

Henry was an 8-year old male treeing walker coonhound found chained to a tree in rural Kentucky. He ended up at HSW in June 2017. He had a cataract in his right eye and was slightly overweight, but was in otherwise healthy condition. For weeks, Henry would spend all his time in the outdoor section of his kennel. Whenever he was taken out of his kennel, he would constantly try to go back – the exact opposite of what every other dog at the shelter does. He would pull on his leash towards the kennel or stand at a door or gate waiting for someone to bring him back. He didn’t eat treats and wouldn’t engage with anyone. For several weeks, he was a puzzle I couldn’t figure out.

It wasn’t until I sat in the kennel with Hank that I finally saw him startle and cringe in response to every door slamming or clang of a metal bowl. Henry’s stoic and disengaged demeanor in all other environments was his coping mechanism that masked his fear of noise. His kennel was the only place where he felt safe enough not to go into freeze. Paradoxically, it was also the only place where he exhibited a clear and immediate reaction to loud noises. The constant whir of cars on Interstate 95, sitting about 100 yards away, acted as white noise that probably helped buffer the noises of a busy kennel. His recovery moved forward once we developed a behavior therapy plan that quieted his environment and included supplements and behavior medications to treat his fear and anxiety. After six long months, a dream adopter took Henry home to a more peaceful life.

Watch the dog in front of you

Depending on the dog, it may take them days, weeks, or months to settle. You’ll see changes in their behavior as they become more comfortable with the environment. To help them adjust, the first step is to create a safe zone that avoids sensory overload and is a predictable escape from stress and activity.

The second step is to remain open, gather information, and be patient. If you’re lucky enough that your dog adapts well to a new life after giving them a little time and space, fabulous! You will have a life of new adventures ahead of you if you have adopted. If you are fostering, then your job is to prepare them for their forever home. Please gather as much information as you can to help make the transition to a forever home as smooth as possible. If you need professional help, the training team at Behavior Vets is here to help you on your journey with your rescue dog.

Thank a shelter worker

I’d like to take a moment to thank you for adopting or fostering a rescue animal during the pandemic. It fills my heart with joy when I hear about all the people opening up their homes to a rescue animal while they are in social isolation. I’d also like to remind you to thank a shelter worker. Most people forget that shelter staff are essential workers because someone has to care for all the homeless animals. They are the kennel staff, vets, adoption counselors, shelter managers, animal officers, educators, and trainers. They are the people who take animals out of harm’s way, often risking their own safety, which is truer now than ever before. They are the people who are behind the scenes doing the dirty work to keep animals fed, healthy, clean, happy, and to find them homes. They play a key role in supporting animals through a stressful transition with their warmth, dedication, and kindness. For some animals who have been neglected and abused, the shelter is usually the first place where any human has shown them love. That caring hand is the most important step towards recovery. From the bottom of my heart, thank you to all the shelter workers across the nation!

References

Broom, D.M. and Johnson, K.G. (2019). Stress and Animal Welfare: Key Issues in the Biology of Humans and Other Animals, 2nd Edition. Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland AG.